I Experience the Jimi Hendrix Experience: Remembering Mitch Mitchell and Jimi

by Sharon Rockey

When I read that Mitch Mitchell, the last remaining member of The Jimi Hendrix Experience, had died in his Benson Hotel room in Portland, all the memories came flooding back. I remembered our conversation aboard the flight from New York to L.A., his soft-spoken, gentle demeanor. While we talked, Hendrix was working his irresistible magic in the background.

When I read that Mitch Mitchell, the last remaining member of The Jimi Hendrix Experience, had died in his Benson Hotel room in Portland, all the memories came flooding back. I remembered our conversation aboard the flight from New York to L.A., his soft-spoken, gentle demeanor. While we talked, Hendrix was working his irresistible magic in the background.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

It was June, 1967. I was working the first class cabin of a Boeing 707. It looked like any other cross-country flight with a cadre of white middle-aged, suited-up, briefcase-toting businessmen.

In those days, first class travel was, well . . . first class –a big roomy cabin with thirty-two comfortable seats, white linen on the drop-down tables, and Rosenthal china and crystal. On that day, with the exception of one vacant aisle seat half-way back, we were full up. Of course, there was the pink semi-circular leather-padded “lounge area” across from the galley, a perk that’s become a dusty memory of a by-gone era—but it was rare for anyone to ride up there.

I was about to close the door for our departure when the gate agent rushed on to announce that we’d have to hold for just a few more minutes because there were three first-class international passengers making a connection. And that two of them would have to sit in the lounge.

We waited. Five minutes passed, then fifteen more. The passengers were getting noticeably impatient and glancing at their watches. You could hear audible sighs and the deliberate snap of newspapers. Finally, the wait ended, but not in the way any of us had expected.

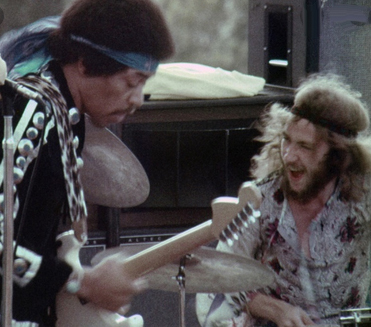

In the next moment, the most outrageous looking man I’d ever seen walked through the front door. He was tall and slender, had a wild Afro hairdo and wore beads, a tie-dyed shirt, and a leather-fringed jacket. My jaw must have dropped an inch or two, but no words would come out.

I’d been raised in straight-laced small-town middle America. I’d adjusted to the fast lane of L.A., but the emerging music and cultural revolution were not yet on my radar screen, and the phrase “Acid Rock” was certainly no part of my vocabulary. So there was no way I could have known that this twenty-something black man was Jimi Hendrix. Yes, he may have been big in the UK at the time, but in the U.S., only the most dedicated potheads would have been aware of him.

Hendrix made his way down the aisle in long confident strides, heading for the empty seat. With every step, you could feel a wave of tension building behind him like a tsunami on the brink of breaking. As he moved, the businessmen eyed him, glaring in motionless silence. None of them said a word; they didn’t have to. The appalled facial expressions and gaping mouths said it all, “So this is what we’ve been waiting for? Our flight was delayed because of this guy? Who the hell is this freak and what is he doing up here in first class? With us!”

Hendrix’s two companions were seated quietly in the lounge area. I was still trying to regain my composure as we taxied down the runway and lifted off for L.A.

During the first hour or so of the flight, I did my stewardess thing, staying close by the galley while avoiding eye contact with all three of them. But I kept picking up a very distinct feeling from the two in the lounge area. There was a kind of unexplainable peace emanating from them, a feeling I couldn’t quite identify. Finally, my curiosity was enough to get me past the faded bell-bottom jeans and unconventionally long hair, and I worked up the nerve to sit down next to them. That’s when I started my conversation with Mitch Mitchell.

You have to understand that after seven years on the job, seven years of being immersed in the L.A./Hollywood mindset, seven years of engaging in upbeat, superficial, and meaningless in-flight chatter, it had become the level of communication I felt most comfortable with. But there was something so real about this guy, Mitchell, something so centered, it felt as if he were coming from a space I’d never experienced before. There were no mind games, no phony facade. It was so disarming, it was all I could do to hold it together. All I knew is that I wanted to understand, needed to understand, what they were all about.

He explained who they were, what they were doing, that they’d just gotten off a flight from the UK and were heading for the Monterey Pop Festival. He said they were billed as The Jimi Hendrix Experience. It was all very interesting, but it still didn’t explain the specific “all about” I was trying to understand.

Then I became aware that what they were really all about was unfolding back in the first-class cabin—where an inexplicable transformation was taking place. As Jimi Hendrix’s energy permeated the cabin, the ethnic, generational, and societal boundaries were evaporating.

By the time we were an hour out from LAX, all the suit jackets were off, the neckties had been loosened, and a few of those buttoned-down businessmen were in their stocking feet. There was a mellow party-like atmosphere—laughing and joking across the aisle, with a smiling Hendrix right there in the mix, while still maintaining his cool.

At the time, I’d never heard the term “contact high,” but that’s the only thing I can attribute to the change that happened—that Hendrix’s energy had temporarily transformed the uptight mindset of those men. I don’t know if his high was chemically induced or not, but the effect was the same either way. I didn’t know what had broken the ice, or how these men from opposite sides of the cultural divide could possibly have found any common ground, or what they were all laughing about. But I did know that something both tangible and intangible was happening.

And the following year, when I heard his song, “If 6 Was 9” with its line, “White-collar conservatives flashin’ down the street pointin’ their plastic finger at me. They’re hopin’ soon my kind will drop and die,” I knew that those words would never apply to the men who had spent six hours with Hendrix at 35,000 feet in the air. The shift that had taken place on that aircraft was unlike anything I’d ever witnessed before during a flight, or anywhere else for that matter.

Something shifted for me, too. Seeds had been planted and the wheels started turning in a completely new direction. Within a few short months, I left the airlines—something I thought I’d never be able to do. I gave away everything that wouldn’t fit into the trunk of a VW bug. I moved out of L.A., spent a month in Laguna Canyon, paid a few visits to the fabled Mystic Arts on Pacific Highway. Then I joined a motley caravan of painted buses, pick-up trucks, beat-up station wagons, and even one second-hand hearse, and headed for the hills of Oregon.

The Jimi Hendrix Experience was the experience I’d been waiting for and didn’t even know it.